11:47 AM – A Critical Incident

It’s a normal weekday in a large hospital. Doctors are preparing for surgeries, nurses are updating vitals, and specialists are reviewing lab reports. Everything depends on systems quietly doing their job.

Then an urgent ticket arrives:

“A surgeon cannot access a patient’s record right before surgery.”

This is not a “we’ll look at it later” bug. This is a “you have a few minutes to figure out what’s wrong” situation.

You follow the logs, trace the call stack, and land inside a method that supposedly checks whether a user can view a patient’s record.

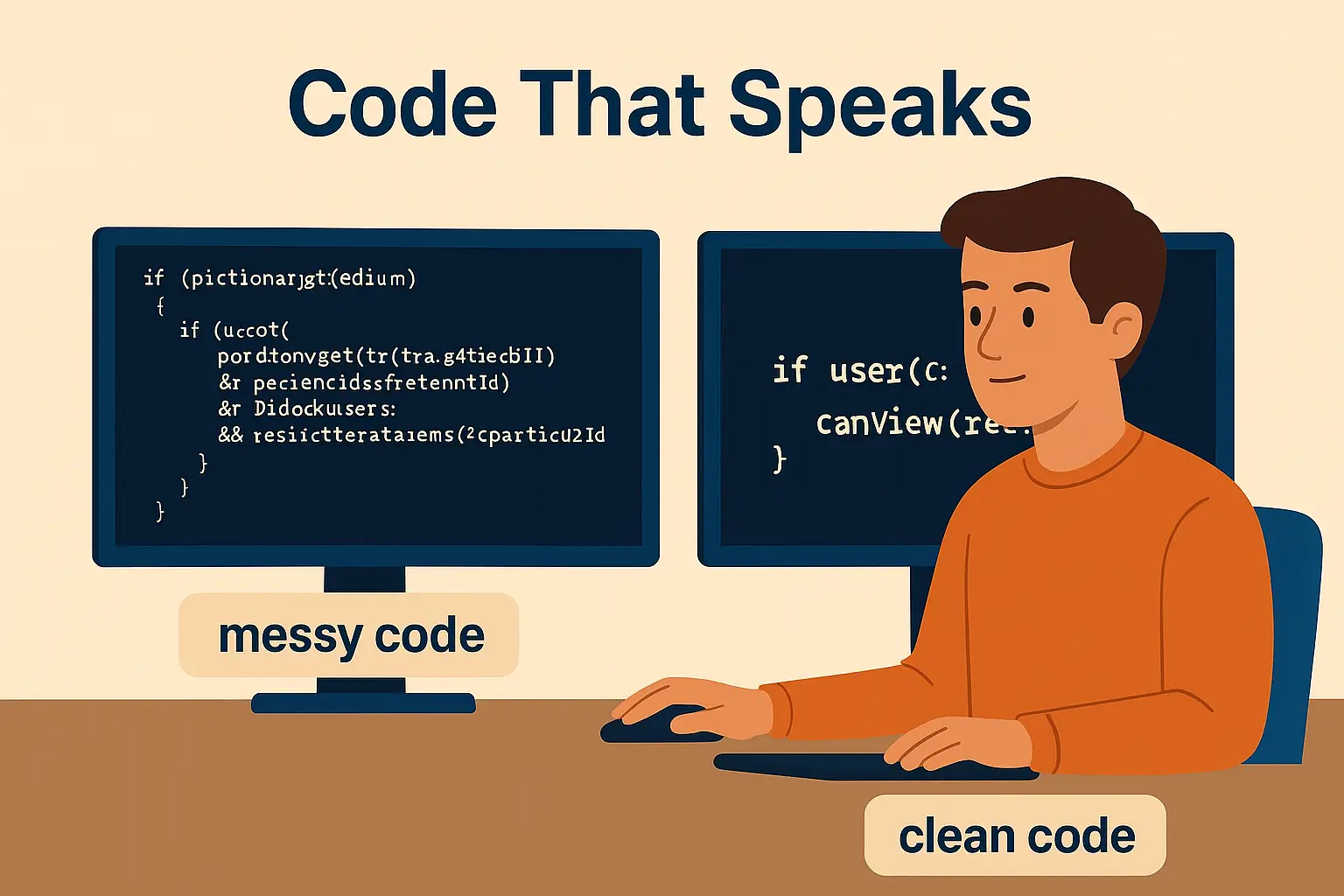

Code That Whispers: When Data Structures Leak Everywhere

Here’s what you find in the existing codebase:

if (_permissions.ContainsKey(userId)

&& _permissions[userId].ContainsKey(patientId)

&& !_blockedUsers.Contains(userId)

&& !_restrictedPatients[patientId].Contains(userId)

&& _roleMap[userId] >= MinimumRoleLevel

&& _departmentMap[userId] == _patientDepartments[patientId])

{

return true;

}

else

{

return false;

}

You can guess that this has something to do with access control, but it doesn’t say that anywhere. Instead you see:

_permissions– probably “who can see what”_blockedUsers– likely suspended or locked out_restrictedPatients– maybe confidentiality constraints_roleMap,_departmentMap– something about role and department

This is code that forces you to read it like a puzzle:

- What exactly is being checked?

- Which part is a compliance rule?

- Which part is just technical plumbing?

Worse, you search the codebase and find multiple variants of the same logic:

// Variant A – missing some checks

return _permissions.TryGetValue(user.Id, out var inner)

&& inner.ContainsKey(record.Id);

// Variant B – focuses only on access level

return _permissions[user.Id][record.Id] >= AccessLevel.Read;

// Variant C – adds a role override, but skips other rules

return _roleMap[user.Id] == Roles.HeadOfDepartment

|| _permissions[user.Id].ContainsKey(record.Id);

Now you don’t have one source of truth. You have several slightly different answers to the same question: “Can this user view this record?”

This is what I call code that whispers. It technically works, but it communicates almost nothing about intent.

Step 1 – Make the Intent Speak

Let’s start by giving the concept a proper name. Instead of scattering dictionary lookups everywhere, we introduce a domain method:

// Application/service layer

if (user.CanView(record))

{

return Ok(record);

}

return Forbid();

This single line already says much more:

- We are deciding whether a user can view a record.

- The how is encapsulated; the what is clear.

Inside the domain, we might push this into an access policy:

public sealed class User

{

private readonly AccessPolicy _accessPolicy;

public User(AccessPolicy accessPolicy)

{

_accessPolicy = accessPolicy;

}

public bool CanView(PatientRecord record)

{

return _accessPolicy.CanUserViewRecord(this, record);

}

// ... other behavior ...

}

public sealed class AccessPolicy

{

private readonly IComplianceService _compliance;

private readonly IDepartmentPolicy _departmentPolicy;

private readonly IPermissionRepository _permissions;

public bool CanUserViewRecord(User user, PatientRecord record)

{

if (user.IsSuspended)

return false;

if (_compliance.IsRestricted(record, user))

return false;

if (!_departmentPolicy.IsSameDepartment(user, record))

return false;

var level = _permissions.GetAccessLevel(user.Id, record.Id);

return level >= AccessLevel.Read;

}

}

This is already a huge improvement:

- Domain terms:

AccessPolicy,IsRestricted,IsSameDepartment. - Intent before implementation: each line reflects a real-world rule.

- Unity: the rule lives in one place, not copy-pasted across the system.

But in a production incident, this still has a major weakness.

Step 2 – When false Is Not Enough

In a crisis, we don’t just want to know “Is access allowed?”. We also need to know “If not, why?”.

A bool return type is too limited. It compresses all the possible outcomes into

yes or no, with no hint about which rule failed.

That’s where a simple but powerful pattern comes in: a result object plus a failure reason.

Step 3 – Code That Speaks and Explains Itself

First, introduce an enum that captures the domain reasons why access can be denied:

public enum AccessFailureReason

{

None = 0,

PolicyRestricted = 601,

UserSuspended = 602,

PendingLegalNotice = 603,

DepartmentMismatch = 604,

InsufficientAccessLevel = 605

}

Next, wrap the result in a small value object:

public sealed class AccessCheckResult

{

public bool IsAllowed { get; }

public AccessFailureReason FailureReason { get; }

private AccessCheckResult(bool isAllowed, AccessFailureReason failureReason)

{

IsAllowed = isAllowed;

FailureReason = failureReason;

}

public static AccessCheckResult Allowed()

=> new(true, AccessFailureReason.None);

public static AccessCheckResult Denied(AccessFailureReason reason)

=> new(false, reason);

public override string ToString()

=> IsAllowed ? "Allowed" : $"Denied({FailureReason})";

}

Now we can rewrite our policy to return a descriptive result instead of a plain bool:

public sealed class AccessPolicy

{

private readonly IComplianceService _compliance;

private readonly ILegalService _legal;

private readonly IDepartmentPolicy _departmentPolicy;

private readonly IPermissionRepository _permissions;

public AccessPolicy(

IComplianceService compliance,

ILegalService legal,

IDepartmentPolicy departmentPolicy,

IPermissionRepository permissions)

{

_compliance = compliance;

_legal = legal;

_departmentPolicy = departmentPolicy;

_permissions = permissions;

}

public AccessCheckResult CanUserViewRecord(User user, PatientRecord record)

{

if (user.IsSuspended)

{

return AccessCheckResult.Denied(AccessFailureReason.UserSuspended);

}

if (_legal.HasPendingNotice(record, user))

{

return AccessCheckResult.Denied(AccessFailureReason.PendingLegalNotice);

}

if (_compliance.IsRestricted(record, user))

{

return AccessCheckResult.Denied(AccessFailureReason.PolicyRestricted);

}

if (!_departmentPolicy.IsSameDepartment(user, record))

{

return AccessCheckResult.Denied(AccessFailureReason.DepartmentMismatch);

}

var level = _permissions.GetAccessLevel(user.Id, record.Id);

if (level < AccessLevel.Read)

{

return AccessCheckResult.Denied(AccessFailureReason.InsufficientAccessLevel);

}

return AccessCheckResult.Allowed();

}

}

Notice what’s changed:

- Each rule is still a simple

ifblock. - Each failure path is explicitly named with an

AccessFailureReason. - The method reads like a checklist of business rules, not a data structure puzzle.

At the call site, we now get both behavior and explanation:

// Application/service layer

var accessResult = _accessPolicy.CanUserViewRecord(user, record);

if (!accessResult.IsAllowed)

{

_logger.LogWarning(

"Access denied for User {UserId} to Record {RecordId}. Reason: {Reason}",

user.Id,

record.Id,

accessResult.FailureReason);

return Forbid(new

{

reasonCode = (int)accessResult.FailureReason,

reason = accessResult.FailureReason.ToString()

});

}

return Ok(record);

During an incident, logs now show something like:

Access denied for User 2017 to Record 9912. Reason: PolicyRestricted

No guesswork. No mental gymnastics. The code speaks and explains itself.

Step 4 – Scaling the Pattern: From if-Forest to Rule Pipeline

As the system grows, more rules appear: emergency overrides, research-only access, time-based locks, etc. You can still keep the logic readable by treating each rule as a composable object.

One simple approach is a rule interface:

public interface IAccessRule

{

AccessFailureReason? Evaluate(User user, PatientRecord record);

}

Then your policy becomes a small pipeline:

public sealed class PipelineAccessPolicy

{

private readonly IReadOnlyList _rules;

public PipelineAccessPolicy(IEnumerable rules)

{

_rules = rules.ToList();

}

public AccessCheckResult CanUserViewRecord(User user, PatientRecord record)

{

foreach (var rule in _rules)

{

var failure = rule.Evaluate(user, record);

if (failure.HasValue)

{

return AccessCheckResult.Denied(failure.Value);

}

}

return AccessCheckResult.Allowed();

}

}

Each rule lives in its own class with its own tests. The combination remains readable and

each failure is still explained via the same AccessFailureReason enum.

Why “Code That Speaks” Matters

In low-stakes code, you can get away with cryptic, tightly coupled logic. In high-stakes systems—healthcare, finance, public services—ambiguity is dangerous.

“Code that speaks” is not just about beauty. It is about:

- Speed under pressure – you fix incidents faster when code is self-explanatory.

- Safety – you avoid unintended rule changes and regressions.

- Auditability – regulators and auditors can understand how a decision was made.

- Evolution – when requirements change, you know exactly where to make updates.

- Developer happiness – you are not forced to reverse-engineer every method you touch.

The difference between:

if (_permissions.ContainsKey(userId)

&& _permissions[userId].ContainsKey(patientId) /* ... */)

and:

var accessResult = _accessPolicy.CanUserViewRecord(user, record);

is not just syntax. It is the difference between code that whispers and code that speaks.

Quick Self-Check

Ask yourself these questions on your next feature or refactor:

- Can I give this decision a clear domain name (

CanUserViewRecord)? - Is the business rule represented as domain concepts, or leaked as data structures?

- Does my code explain why something fails, or only that it does?

- Is the logic in one place, or duplicated across services/controllers?

- Would someone new to the domain understand the intent just by reading the method?

If the answer to most of these is “no”, you’ve found a chance to make your code speak more clearly.

Mini-Quiz: Did This Article Speak to You?

-

Why is returning a plain

boolfrom business rules often not enough?Show answer

Because it hides why the rule failed. In incidents, you need the reason as well as the outcome. -

What makes

user.CanView(record)better than a nested dictionary lookup?Show answer

It expresses the domain intent (“can this user view this record?”) and hides implementation details. -

How does

AccessFailureReasonhelp operations and audits?Show answer

It provides explicit, categorizable reasons for failures that can be logged, monitored, and reported. -

Why is scattering access checks across multiple services risky?

Show answer

It leads to inconsistent rules, hard-to-trace bugs, and makes changes error-prone. -

What is the core idea behind “Code that speaks”?

Show answer

Code should reveal intent in domain language, not force readers to decode algorithms and data structures.